It is the first night of December and my window is a rectangle of pure, inky black. It’s as if the world has been erased and I am floating in a box of light. As if this small room is all there is. I type black words on a white screen and try to remind myself that I’m still here. Everything is still here. I’m writing this to prove it to myself and to you.

I have a longing to tell you stories. That’s what everyone wants, isn’t it? A good story? It’s why people come to writing in the first place, perhaps why you come to me. It is a truth that threatens me with inadequacy when fatigue comes and leaves me as empty as the night. For three weeks again, I have barely moved from my pillow except to go to hospital and back — treatments and checks for the inevitable infections I always get when run low, kidneys then chest, the grind of slow recovery. “You always seem to be sick.” I hear, a voice like crossed arms. It’s true. So what then?

I do not believe long-term illness necessarily makes me uninteresting as a writer, but I worry that a life of fatigue does. I worry it strips me of colour, movement, interaction, humanity. It isn’t just energy or activity that abandons me when I’m particularly fatigued, it’s words, it’s stories. Oh, thoughts remain, plenty of them, but they’re just footprints walked round and round in circles, overlapping, muddied, obsessive, no real use to anyone. I know not to dedicate too much time to them anymore.

The drive remains like a heartbeat: to let go of thoughts, to find stories instead. Perhaps I just want to bring you something good in the dark. Perhaps I am afraid that if I don’t, I will be forgotten. Perhaps I am afraid that if I don’t, other, brighter people will race past me with their more interesting lives and their more efficient paths. And so, I tumble them out here — my stories — like a purse emptied out on a counter, loose change pushed forward, hoping it's enough.

A girl lies in bed. No, I can’t call her that anymore — grey streaks her hair, middle-aged weight sags her chin and her belly. A woman then. A woman lies in bed, pale against her pillows. She is holding a hand mirror up to her face and she’s saying, “I love you, I love you, I love you,” to what she sees there as waves of shame and comparison attempt to batter the shore of her, held back by this powerful, powerful spell. The woman is me. She is tired of telling stories about herself.

Her mother — no, stop this, I am something good, my stories matter — My mother sits next to me in a hospital side room. Her body is small and familiar. My cheeks are red and her cheeks are red too. I want to touch mine and then hers, just softly, just to draw the link in the air. I am folded in two, trying to be cheerful. Mum reads her book about The History Of Life On Earth, reading aloud chunks every time she gets to a part that surprises her or delights her, which is often. Early humans, newly upright, care for each other, make art, make homes. It feels much easier to be cheerful as the long evening wears on.

Before I got this sick again, I sat at a table in the community centre and was joined by the shuffling steps of Flo. She is older than my mother. She has a face like paper that has been scrunched and thrown away, and she has a yellow voice, thick with nicotine. We drank our tea together and she proudly showed me her new blue boots, flowery and shining with glitter. She’d only really come out to show them off. They were too big for her feet so they could fit around the swell of her lymphedema but they looked just fine, they looked brilliant. As we sat, she told me how, once, she decorated her whole house, back when she was young, back when her terrible ex husband was always away with work. She told me how she did it all alone, trimming the overgrown garden on her hands and knees with scissors. She said, leaning forward, “and when people came round, they said I can’t believe it. I can’t believe you did all that.” But I could believe it. I really could.

When fatigue drowns me, the fact that life must continue somehow both overwhelms and saves me. I must remain both the carer of myself and the person in need of care and that is hard but each role equips me better for the other. To empty the dishwasher, to load the washing machine, feels like labour almost more than my body can hold and yet, and yet. Day after day, I lift and stack, feeling ridiculous, my heart beating time like a heavy drum driving the legion of me forward. I feel every plate, every shirt, every piece heavy in my hands, and I breathe and lift and move, like building a wall. It is a wall of deciding care matters. It is a wall of ‘not giving up just yet’.

I am hunched again in the tiny A&E, artificial lights cutting and unkind. A family arrives to queue at the desk and, parked nearby in my wheelchair under my bulky scarf, I watch, I listen, I can’t help myself. They have been rear-ended by another car. The three young siblings stand in front of their parents in descending heights, blonde hair tumbling down their backs, faces red with crying but not crying now, two each with an arm round their middle sister. Her mouth stretches open in misery, her arm is in a sling, and either side they hold her — bigger sister, littler brother — and they stroke her hair, rub her back. Their parents’ arms, the children’s free hands, are amassed with stuff: soft toys, blankets, all their best things.

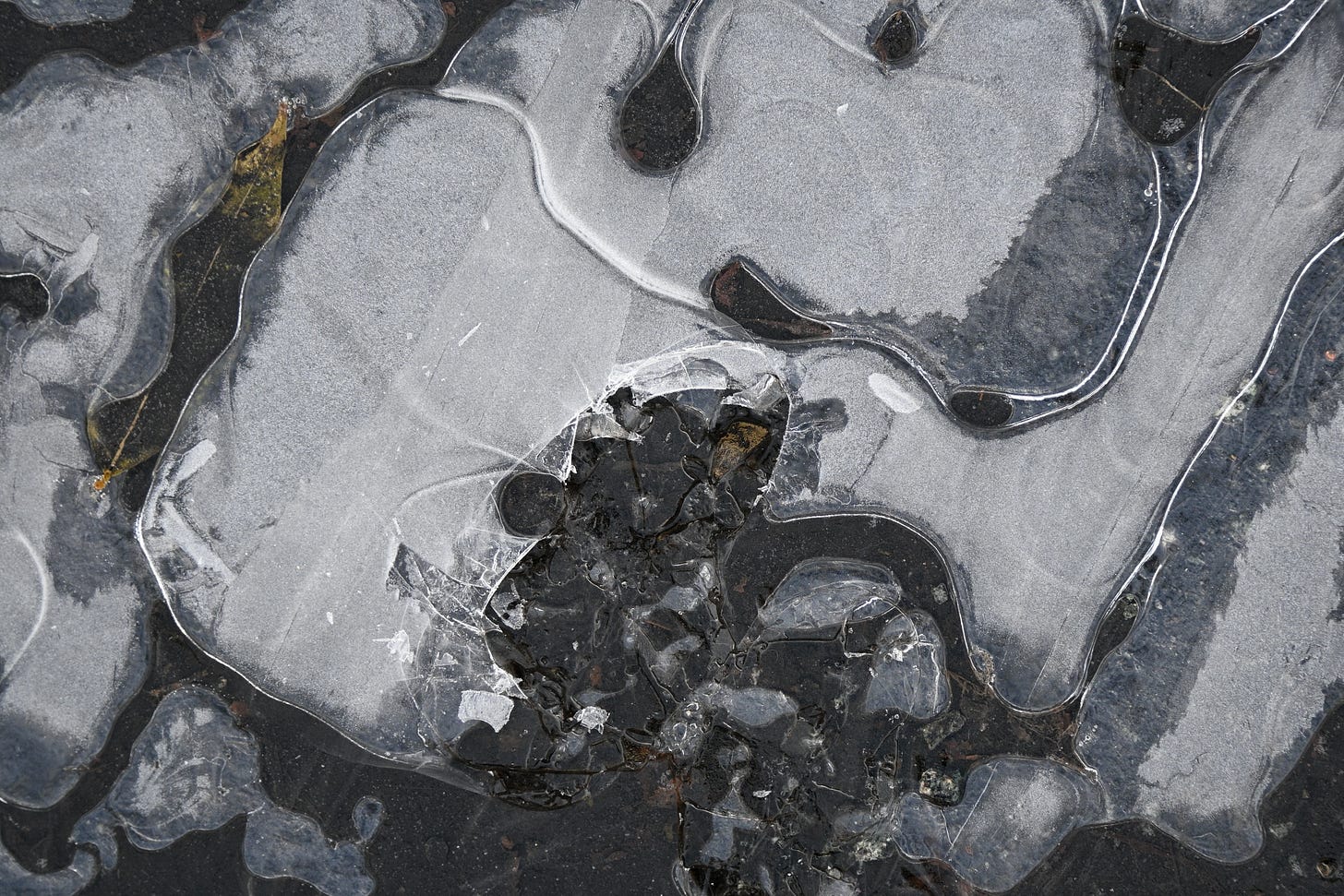

Back home, there are three snails in the fish tank in my bedroom: big, middle and small, like the siblings in the waiting room. They patiently clean the glass of algae that I have not been well enough to remove, leaving zigzag patterns like writing. When I go to the toilet, I put my hand to the glass and whisper, “thank you, thank you friends.” They continue their slow circuits, leaving messages I will never get to understand. They are circled by my huge, fat fish, silver like a ghost now in his old age. Sometimes I lie in bed and imagine him rising and swimming around my head, weaving a spell of protection, of safety.

It has snowed in Denmark and, over video, Fraser is showing me all the footprints on the lawn, panning the camera carefully from print to print so I can see, so I can drink them in. Cat, solitary bird, a hare, perhaps? We reach a sudden dance around the apple pile, a veritable storm of four-pronged stamping. “I love you,” he says, turning the screen to show himself, his face a message all its own. “I’ll be there soon,” he says. “Hold on.”

I remember the older female doctor who, just briefly, put her hand to my back with such gentleness to steady me as I left her consulting room in the middle of the night. “I am glad to have met you,” she said. “I do so hope you feel better soon.” It is another doctor, a different day, and he wheels me carefully to the exit after midnight, tucking my scarf closer to me. “I don’t want you to get cold,” he says. Neither of these people speak my own language as their first and I think again of how irrelevant language is, really, when held up against the way we move, the way we touch, the things we do, the soft, lilting sounds and gestures we all can make.

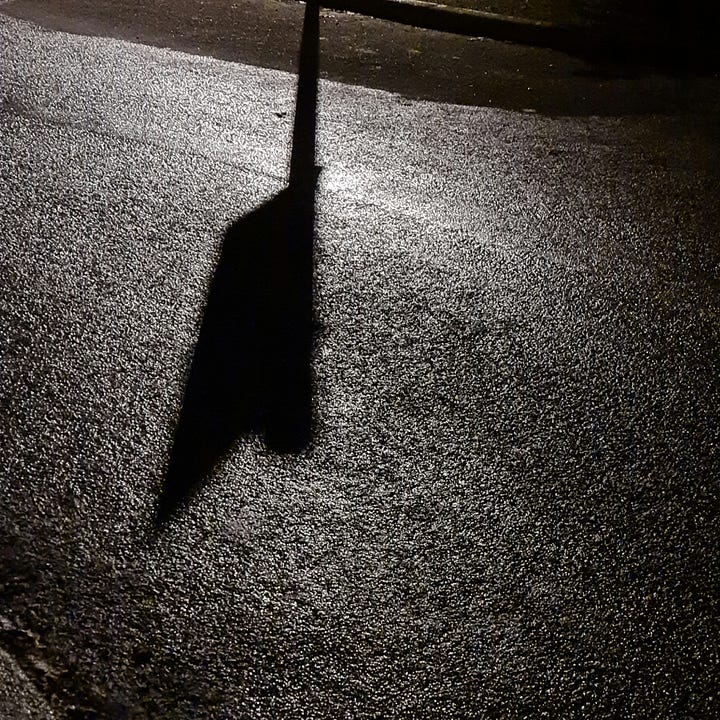

Sunlight. Gold and soft. After days of cloud, it arrives in my dark, hidden room to stripe my arms and legs like a tiger and, feeling stronger, I stalk the house with my new pelt. Outside, the walls quiver with the shadows of leaves twisting in the breeze, leaves I can’t see directly, all talking with each other, all out of sight yet here, here with me. Back in bed, exhausted, I sit and think about the enormous generosity of light’s touch, the way it spreads more life into places with less, like butter. It gives me courage.

It is a new day. I brave a trip outside, just to the tree and back. The world still spins as I walk, blue sky above, and a seagull, white, white like a splayed hand, flies above me, hovering, guarding. Under my unsteady feet there are leaves stamped into patterns on the pavement like fabric. Reaching the tree, I inch up my spine just a little to let the top of my head touch the overhanging bare branches, in blessing, in love, and I feel such a rush of gratitude for this caring, generous world, that tears spill then, spill and fall and keep falling for the first time through all these long weeks.

There, my purse is empty.

After a weekend when the world has shopped and shopped and shopped, a part of me cannot help but wonder whether this will be enough. I think of all of us sitting today, staring at the mess of our lives, wide-eyed, wondering how to pull something entertaining from it, quick, before we are deemed insignificant or boring and dismissed. Quick, make it impressive. Quick, make it clever. Has it always been like this? Have we always been under this much pressure?

As time goes on, I think I am drawn less and less to people bending themselves and their lives into polished shapes they can sell. I do not want stories of transformation. I don’t even want to be entertained anymore — how cynical it increasingly feels to demand we all be entertaining all the time, in this world, in these bodies, these lives.

No, I believe what I crave now, and I crave it like a thirsty animal, is simply the honest exhaustion of a raised arm as someone points to something true, something raw and wondrous, inexplicable in its perfection, someone brave enough to let that be enough.

Look, look, no not at me, at this, at this.

Look. Look. Look at all the love there is.

You’re reading a bimblings — my heartfelt offering to a generous universe. If you subscribe, you’ll receive one or two posts like this a month. They’re always free and offered with love. Upgrading to a paid subscription is entirely voluntary but a vital source of support to help keep me writing and to protect my livelihood. Paid subscribers also receive occasional, extra, behind-the-scenes news about my personal life, book-writing, art practice, loves and losses, plus more on how I navigate life with a body that doesn’t work so well. If subscribing isn’t for you, perhaps you’d like to buy me a coffee instead? It all helps me and my family enormously. Thank you so much for being here.

Dear Josie, I am happy every time I see a new offering from you, not because I expect something new or exciting every time, or because I count on something coming on a regular basis. I am happy because it comes from someone honest enough, brave enough and generous enough to write and create in such a way that her spirit shines through always. Even when you yourself may feel it is not so, I think I am not alone in feeling touched by you in the heart space in which we are all connected. That is quite a gift you trust us with and it is definitely enough. Once touched, no need for many words. Once given, such a gift becomes a treasure.

Any time I tell a fellow chronically ill person that a limited life can be a good life, I recommend them your book and this Substack and I tell them how much your perspective on life helped me to find my own ways to live a good life, a big part of it being a greater appreciation of nature. I will never forget the difference you made.

You recommended I get a magnifying glass on your moss post and so I did and I've had a wonderful time looking at moss and plants and tree bark. Last week I got to use it to look at everything covered in frost and it was incredible to have that view that I'd never seen before. So thank you for adding that joy to my life!

I hope you'll get some respite from the infections and hospital trips soon.