Bridge

This is a love story.

It began with a bridge, a prayer thrown to the wind, although I didn’t know that to start with. The first I know of it is when I stumble and find myself face to her face. “Oh!” I say and pull back. I had nearly walked right into her.

My house is too small for a washing machine. It lives, instead, in the old outhouse in the back yard, behind a rotting panel door, the black paint peeling to reveal an older life: a blue that makes me think of hospital walls. I am not good on my feet and my few steps from the back door, the laundry basket balanced on my hip, are always unsteady. My legs are left dew-wet from the spent hydrangea that leans over the path and from the long tendrils of the passionflower that grows over the kitchen window. The passionflower has pushed itself through the bottom of its plastic pot, right down under the slate path and into some secret earth below, to grow colossal. It is from one of its many reaching fingers that the web starts. A long thin line stretches to the brickwork opposite, fixed with invisible anchors. The spider web proper sits beneath it. Round and perfect, over a foot wide, right across the outhouse door. She, the spider, sits in the middle, bouncing slightly from the impact of my intrusion.

She is an orb weaver. I know her to be female from her fat brown body and neat head. The pattern on her back makes a white sword, pointed to the sky. The web is immaculate, fresh and new. It blocks my path, but I cannot bring myself to disturb it. And so I bow, awkward, and ducking underneath it as best I can, open the outhouse door as little as possible to squeeze in and load the washing machine. The edge of the door pushes against the web but doesn’t break it. I retreat back out again the same way, my back low, hoping I don’t topple. I stand once I am clear and wish her fine hunting. She sits, impassive, in reply.

This then becomes our routine. Each day I take my green laundry basket, full of school uniform or bed sheets, socks and t-shirts, and I greet and duck and bow like an acolyte. Later in the day, I return and do the same. One morning I find she has hitched the web a touch higher allowing for less contortion on my part, and I thank her. My words become less formal day by day. Sometimes I go out without the laundry, just to look at her.

One warm, bright day, I hang the wet washing on the line rather than spread it on the high ceiling airer inside. The washing line stretches from the outhouse to the post at the end of my small terrace garden and is festooned with smaller webs, stretching between colourful pegs I have left pinched there. I brush the silky bunting away, feeling guilty, glancing up to check on my new friend’s web for the hundredth time, the shine of it only just visible against the outhouse door, her brown body a smudge in the air. I tell myself I am allowed to have a favourite. I reach for a peg to secure one end of my duvet cover and discover a smaller orb weaver crouched inside the rounded plastic. I check each peg and find a spider in most of them, curled and patient. Little sisters, little brothers. I apologise and replace each peg carefully.

Through all this she sits. I never see her move until one evening. I have gone out to say goodnight and find her front legs busy, a great white mound drawn close to her as she knits it closed. I peer to see, make out black and yellow, a wing angled, broken. A wasp! I feel awe and pride. A couple of days ago, I had placed a chair near, so I sit on it a while, watching the swift spin of her hands, wishing I’d brought my own knitting, wondering if I did, whether her dark eyes might turn to watch me, as I watch her, wondering if she would perceive some kinship, but my legs are too sore to go back for it and the streetlamp over the wall is beginning to blink. I have cast on a round shawl in reddish-brown, the colour of conkers and the leaves in the gutters. I knit it in bed instead and think of her.

Sunday comes, and my boyfriend in Denmark goes for a walk in the woods. He sends me photos of the misty early September hours, the tall trees, the grumpy frogs in the leaf litter, while I lie, safe but in pain in my bed, my body furious as it often is, my unsteady legs even less reliable than usual. Everywhere on his walk there are webs: wide, lacy nets and sheet-like cat's cradles, all covered in diamonds. “It’s on mornings like this that you realise the world is mostly spiders,” he says, before the day warms and they all disappear, unseen again. I find the thought immensely comforting. I am an unseen thing, often, too. Distracted by my body, I drop a stitch on my knitting, watch the lace collapse and groan. It takes me two hours of careful tending to repair.

I am still full of these things when I go outside later, the late laundry basket on my hip. I am so preoccupied and elsewhere, that I don’t realise until I feel the silk against my face. I stumble back, horrified, to see I’ve torn the bottom of her web, concentric circles halved in a snap. All these days of vigilance and I forgot in a moment. She has scuttled under the passionflower leaf that holds an anchor point. I swallow hard, feeling terrible, remembering my own lengthy repairs. I whisper words of apology. It’s not like she’ll care — she’ll be used to rebuilding over and over, and the strong, important bridging web that marks her territory remains —and yet I am angry at myself, at how easy it is to be thoughtless and hurt the ones you love. I know a web broken too often will mean she’ll move elsewhere. The remaining day's words and deeds feel like bulldozers. I speak them, steer them, carefully.

The week is wet, then windy. The replacement web she built after my destruction is first battered by heavy rain until only a small moon of it remains. I sit inside, day after day and realise that without a web, she won’t be able to feed. I hope her larder is well-stocked. I think of the wrapped wasp and wonder how long these things last. When the rain clears but the wind moves in, I go out to find her web renewed but changed, angled to offset for the blow and shove of it, and marvel at my engineer’s insight and ingenuity, but by tea time it is sheered again, only that single first bridge line holding on. She sits and waits it out — meteorologist and engineer, both — upside-down under the leaf I can now pick out from the mass in an instant. Fine webbing has pulled it into a curled, green cave. Her legs are drawn in towards her. I wonder if they ache in bad weather like mine do. She is bigger than I remember. She is very, very still.

It seems striking, suddenly, to love a creature I have no way to care for. I cannot offer food or shelter until the storm passes. The spider’s ways and mine are so alien and removed from each other that there is no overlap, no common ground. Mammals I could leave out loaded dishes for. Birds, I could fill feeders. Even a bee I could offer sugar water to; a fly, some cut fruit. It is humbling to my ego. I cannot be special to her. I can do nothing but be careful and appreciative but I know that’s still something, that it still matters, especially in the absence of no other way to care. The weather clears a little but she does not come out.

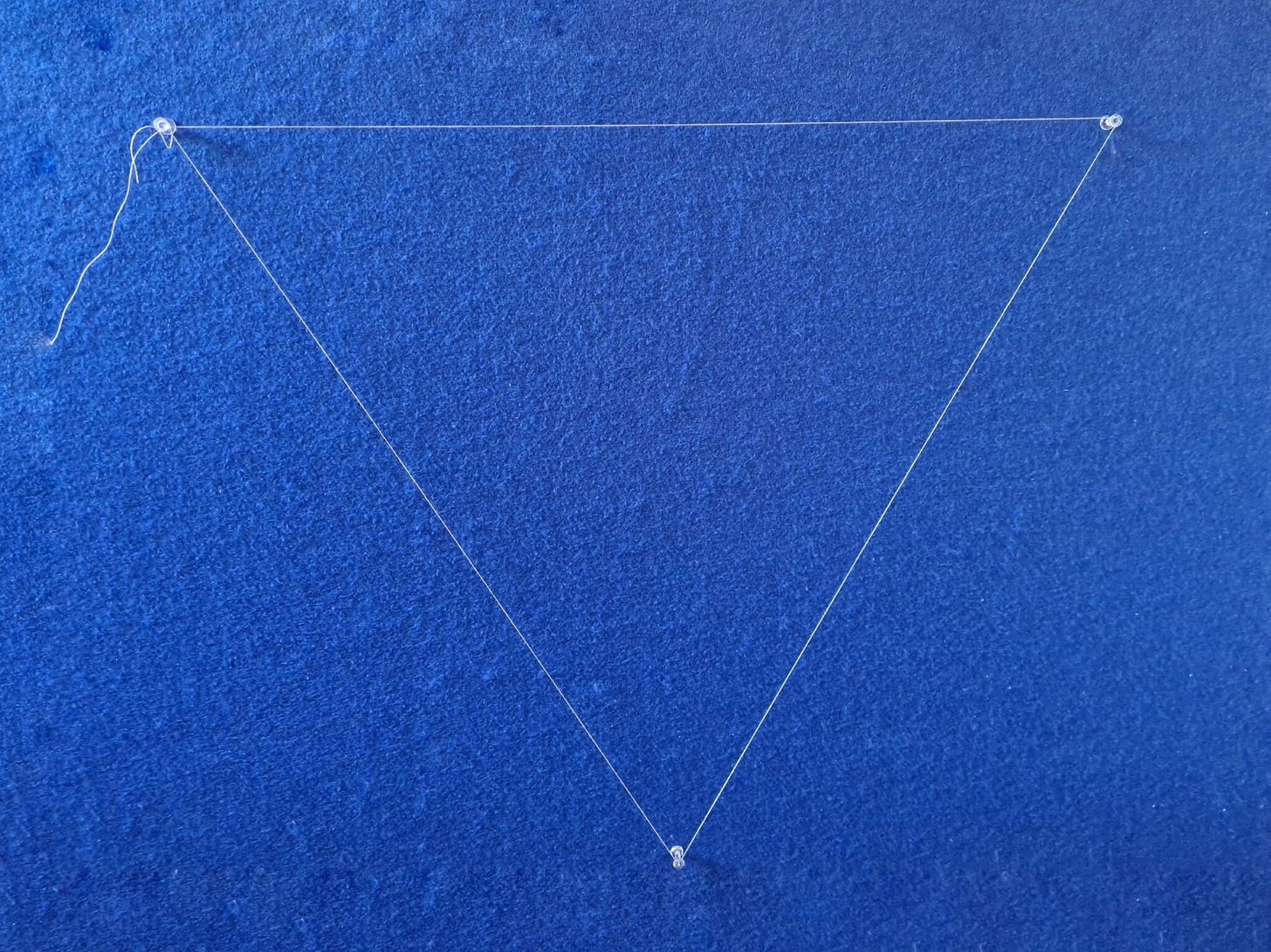

By the time Friday afternoon rolls around, I am decided. I sit on the floor of my room in front of a notice board with a roll of white thread and a box of drawing pins. I know I could cheat and pin easy anchor points around in a circle, but I want to do this properly. I have done my research and learned that a spider’s web begins with that first, strong bridge from point to point, a length of web thrown into the breeze and left to catch, to join a gap, a process known as ‘kiting’, so I make that line first. I allow myself one anchor point at the bottom, and join it to the bridge in two places, picturing her abseiling down to do the same. I look at my reference photo and add frame threads, then the spokes of the radius. Slowly, I begin the auxiliary spiral.

I sit for hours. I am clumsy and slow. Every time I begin to feel assured of the neatness of my spiraling circle, I twitch, or catch the thread on a drawing pin, and watch the spiral spoil. I spend half the time teasing the threads apart as they stick to each other, or lamenting that one of my radii has fallen slack somehow and thrown off the tension. I cannot believe how difficult and fiddly it is, even for an accomplished knitter, but then I am as big as a mountain. I think of her fine, clever legs. I think about the fact that no-one taught her this, that somehow she just knew, that the knowledge was spun into her.

I rest occasionally to read about araneus diadematus — her grander name. I feel my heart beat hard in my chest when I discover that soon, very soon, she will lay her eggs and her life will stop, all her work done. I think of her hunched, swelling body, her abandoned web, and wonder if it has already begun. I comfort myself by thinking of it in new terms: she fought that wasp as an old lady. All those orb webs that characterise our early autumn mornings are made by pensioners — survivors of the year and all its hardships, one last, glorious display. I go back to the thread of my web, hooked, caught there as efficiently as any fly, wanting to understand, to find my way right to the heart of what all this means.

I work until it gets dark and fall into bed, sore and moved, knowing I will never have the skill to finish it, that I will never be able to look at a spider’s web in the same way again.

I wrote these words and checked on her, under her leaf. The day is blue and fresh. Three new bridges cross-cross the gap, joining the first. They shimmer in the air, stronger than steel; fistfuls of prayers thrown and caught, because why not, why not be hopeful in the end? I send my own prayer with it. That she might perceive, somehow, in these last golden days, that she was noticed, treasured, known.

You’re reading a bimblings freebie post — my heartfelt gift to the universe. If you subscribe, you’ll receive one or two posts like this a month. For more behind-the-scenes news about my personal life, book-writing, art practice, loves and losses, plus more on how I navigate life with a body that doesn’t work so well, please do consider upgrading for a small monthly fee. Alternatively, perhaps you’d like to buy me a coffee? It all helps me and my family enormously. Thank you so much for being here.

I found your Substack through the Beyond questionnaire and am so glad I did! Your answers there felt beautiful and resonant to me, and this post here was a delight. I felt pulled into a slow, mindful cadence reading it. It just so happens that I sat and watched a spider capture a wasp a week or so ago. The wasp was understandably frantic (or so it seemed) and moving furiously, but the spider was patient and strategic. In the end, she won the meal. I watched for maybe fifteen minutes and wished I could have stayed longer. It’s so easy to miss those little moments - and all too often, I do!

An extremely moving, beautifully written piece.